Our Strategy

Coordinated Advocacy

We will work with individuals and organisations in Africa to create a coordinated strategy around the decolonisation of global health practice. We believe in the catalytic effect of coordination. Therefore, we aim to offer a mechanism for people and organisations to work together in implementing this coordinated strategy.

We know that we can’t rely on other people’s sense of ethics or self-interest regarding decolonising global health. Therefore, we intend to amplify the pressure they are feeling.

We will apply pressure on three main constituencies in global health practice − funders, governments, and the media (including academic publishers). These constituencies hold the most significant influence over global health institutions and practitioners. They are also complicit in perpetuating various manifestations of coloniality in global health.

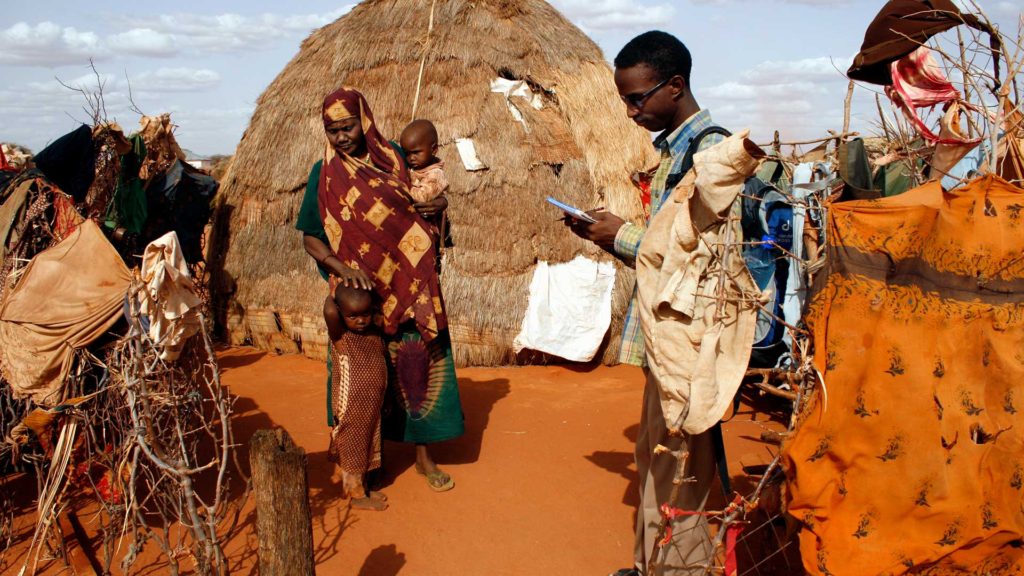

For example, Funding Agencies that insist on North-South collaboration as an explicit or implicit condition for grants perpetuate “saviourism” which is enabled by the asymmetrical power relations between global health practitioners from HIC versus LMIC. Some funders have also promoted “copy-pasting” of global health solutions from HIC even when there has been no rigorous evaluation of their potential impact in an African context.

On the flipside, chronic underinvestment in health by several African governments has created an enabling environment for African global health practitioners to be significantly dependent on external funding.

Not forgetting the African and international media who are sometimes guilty of perpetuating colonialist notions of expertise that fail to recognise the geopolitical imbalances of global health education and career progression.

Strategic Communications

We will seek to create and promote safe spaces and forums for frank and open conversations about decolonising global health.

At the individual level, we aim to give a voice to the innumerable African global health practitioners whose voices have been drowned out, whose expertise have been trivialised or patronized, whose qualifications have been disparaged and whose career progression have been restricted. As well as those that have suffered various forms and levels of dehumanisation such as blatant racism at work, or the humiliation of having their visas to attend scientific conferences denied, or the indignity of being forced to “collaborate” with a HIC counterpart just to stand a fair chance of getting their work funded or published, to mention but a few. Indeed, we hope to empower African global health practitioners to shatter the “mud ceiling” and to have legitimate opportunities to advance beyond the “brown ghetto”.

At institutional level, we hope to support African global health organisations to acquire more power and autonomy, where applicable. As much as possible, African offices of international organisations should have the full authority and corresponding financial resources to make decisions and implement an African agenda. More power and autonomy to African offices will enable international organisations to be more agile and to adapt rapidly and appropriately to local needs.

We will also put pressure on donor organisations to drop all mandatory requirements for LMIC institutions to partner or collaborate with those from developed countries. We will also strongly discourage them from overtly or covertly nudging African institutions into “North-South” collaborations. The intent is not to discourage these kinds of partnerships but to ensure that African institutions/practitioners come to the decision entirely on their own and without any undue influence or fear of repercussion.

Patient Capital

We will persuade African governments and their development partners to invest in reforming the global health landscape. We appreciate that tackling the root causes of coloniality in global health will require time, patience, and considerable resources. Furthermore, there will be a need for multisectoral mobilisation and collaboration to address the underlying economic and political power relations between HIC and LMIC that are essentially at the heart of coloniality in global health.

This kind of multisectoral mobilisation will also ensure that the decolonisation movement does not neglect other social vulnerabilities such as gender inequity in global health practice. For example, African women generally constitute the bulk of the health workforce but are underrepresented in global health leadership locally and internationally. Decolonising global health in Africa will be incomplete and ineffective without gender and intersectorality at its core.